“How do you memorize all those pieces!?”

Wherever I perform in the world, this is one of the questions I get all the time as a pianist. However, no one has ever asked me WHY I memorize all those pieces. When and why did memorization become established as our piano performance practice? I am a pianist who has attained a doctorate, determined to find out for myself.

As soon as I started my research, I realized that same “why” that my audience members neglected was also missing from musicology. Perhaps that was why. Many of what people commonly believe about the history of memorizations turn out not to be based on any historical evidence. For example, Liszt and Clara Schumann are not the pianists who started the tradition of memorized performances. The genesis of memorization as a piano performance practice took place within the context of major technological, political, aesthetic and philosophical movements in the Age of Revolution. All I want to accomplish through this brief essay is to whet your appetite for this fascinating subject and encourage further research.

In 1787, the then 16-year-old Beethoven (1770-1827) visited Vienna for the first time. Although there is no written record, there is an anecdote from that visit that is still popular today. In it, Beethoven pays a visit to Mozart (1756-1791) and improvises for him. Believing it to be a memorized showpiece, Mozart is dismissive. Sensing this, Beethoven asks Mozart for a tune to improvise on, winning Mozart’s acknowledgement of the youth’s talent. Regardless of the historical legitimacy of this anecdote, there are two takeaways that are pertinent to our understanding of the history of memorization in it. One, that they both considered improvisation to be a more admirable skill than memorization. And two, that the concept of memorization was not news to either of them. This reminds us – Mozart’s musical memories yielded many anecdotes as well, some with evidence others without.

Memorization was a practice that became mainstream over a course of a much longer time period that we tend to think. It coincided in timing with several notable phenomena like the disappearance of improvisation as a performance practice, the emergence of non-composing performers and non-performing composers, and the ritualization of concerts.

For a long time, music was considered to exist only when it was being performed. When you think of music this way, then performers become more important than composers, and performances more important than the score. I imagine the score then to have been like a recipe to a dish, a recommendation to develop your dinner on. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788), in his True Art of Playing Keyboard Instrument (1759), complained about both the audience expectations for improvisation and the risk it posed to the integrity of a composition: “The public demands that practically every idea be repeatedly altered, sometimes without investigating whether the structure of the piece or the skill of the performer permits such alteration. It is this embellishing alone, especially if it is coupled with a long and sometimes bizarrely ornamented cadenza, that often squeezes the bravos out of most listeners.”

Europe in the 18th century provided fertile grounds for the flip to occur in this power dynamic. It was the Age of Revolution. The power of the church and courts was rapidly declining, if not overthrown by force. The industrial revolution resulted in explosive urbanization. In the midst of these great changes, people are starting to question what our humanity is, and what our individualities are. What distinguishes men from machines? What is creativity? What gives me irreplaceable value? What is creative genius that stands out from a crowd?

It is within this context that aesthetics as a branch of philosophy, and the concept of fine art, is established. Fine art is to pursue the purely abstract notion of beauty, without any practical purpose or application. When music was included as one of the branches of fine art, alongside painting, sculpture, poetry, etc. that became one of the catalyst to flip things around. In order to have a tangible form, that is equivalent to a painting or a piece of sculpture, it was decided then that music was its score, and not in the ephemeral performance.

And then, the game changer Beethoven caused a stir in the history of music.

The notable improviser Beethoven’s compositions challenged all traditional notions about music. The number of notes, registers, texture, length, dynamic range – everything was more, and bigger in his pieces. The demands his music placed both on their players and listeners eventually became widely appreciated, appealing to their Bildung – the German spirit of self-cultivation. Musicologist Sanna Pederson attributes the national celebration of Beethoven’s creative genius partially to their need to promote their artistic spirituality and cultural superiority due to the country’s slower progress in the areas of politics, technology and economy compared to other European nations.

In order to understand Beethoven’s great music, one must understand the inevitability of each note in the grand scheme of the architecture of its entire piece – a concept known as formalism was promoted by people like music theorist A.B. Marx, and music critic E.T.A. Hoffmann. Formalism requires reading of the score to appreciate the music. As though to appeal even more to their spirit of Bildung, Beethoven’s demands for its players become more difficult and specific. In the course of this development, his famous “no si fa una cadenza (do not make a cadenza – cadenza was a place in concerto where the soloist was given the freedom to improvise traditionally)” indication in his fifth piano concerto “Emperor” Op. 73 (1811) becomes historically symbolic.

Mendelssohn (1809-1847) could play from memory all of Beethoven’s symphonies by the age of eight. Many of the first records of memorizations are also of Beethoven’s pieces. This is not surprising. The more difficult the piece, the more practice time a pianist would spend on the piece. Also, the structure of the piano does now allow for the pianist to look at the score and the keyboard at the same time – another reason to commit a difficult piece to memory.

Czerny (1791-1857) was ten years old when he played the Pathetique Sonata from memory and was accepted by Beethoven as his pupil. Czerny had a phenomenal memory that Beethoven also attested to his in his letters of recommendation. However, Beethoven himself cared more about the faithfulness to the score than to have it be memorized. In his On the Proper Performance of All Beethoven’s Works for the Piano, Czerny recalled an incident from his twenties,

playing the Quintet for Piano and Winds at a concert:

[With] the frivolity of youth, I took the liberty of complicating the passage work, of using the higher octaves, etc. Beethoven rightly reproached me severely for it, in front of Schuppanzigh [the presenter of the concert and a violinist], Linke and other players. The next day I got the following letter from him… “I simply lost control yesterday, and I was sorry about it as soon as it happened. But you must forgive it from a composer who would rather have heard his work as it is written, as lovely as your playing otherwise was…”

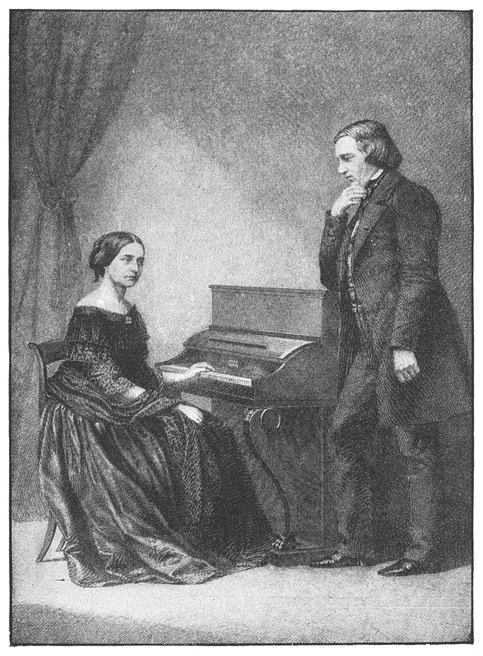

E.T.A. Hoffmann comes up with the concept of Werktreue (true-to-work) spirit – a veneration of the canonized work reflecting the performer’s scrupulous study and internalization of the score. The ritualization of concerts around the same time can arguably be attributed to this spirit at least in part. In the ritual worship of canonized composers, the players serve as the priests, or an empty vessel to channel the music, or the composer the oracle. In this type of ritual worship, memorization becomes a way to internalize the score and to express the player’s devotion to the composer and the music. Further, in this format, a composer playing his own pieces would not work. Instead, revival of dead composer’s music began to take over performances of contemporary works. At the same time, female pianists begin to emerge en masse. If it was not as creative composers, but as recreative players, women – who were considered to lack creativity – can be accepted on stage as professionals. The epitome of these priestesses was Clara Schumann.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896) was regularly regarded by music critics, among them her husband Robert, as a “priestess” “angel” “prophet and “St. Cecilia” and wore dark and modest dresses for her performance, befitting to her role. According to the database of over 1300 of her concert programs from her debut as a prodigy in 1828 to her last public concert in 1891, she focused on performing her late husband’s works as well as other deceased composers such as Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Chopin, playing her part in the canon formation. In addition, by insisting on memorized performances despite her increasing fear of memory lapse as she aged and injuries that were possibly psychosomatic, she helped promote memorization in the next generations of pianists. However, her 1837 performance of Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata as the first memorized performance is simply not true. She had a unique childhood education, based on Rousseau’s and some other pedagogical philosophers that were adapted by her father. For the first two years of her lessons, she learned to play scales, chords and to improvise and transpose, before she was taught to read notations. Clara started by dealing with the piano and the music with her hands and ears without the score.

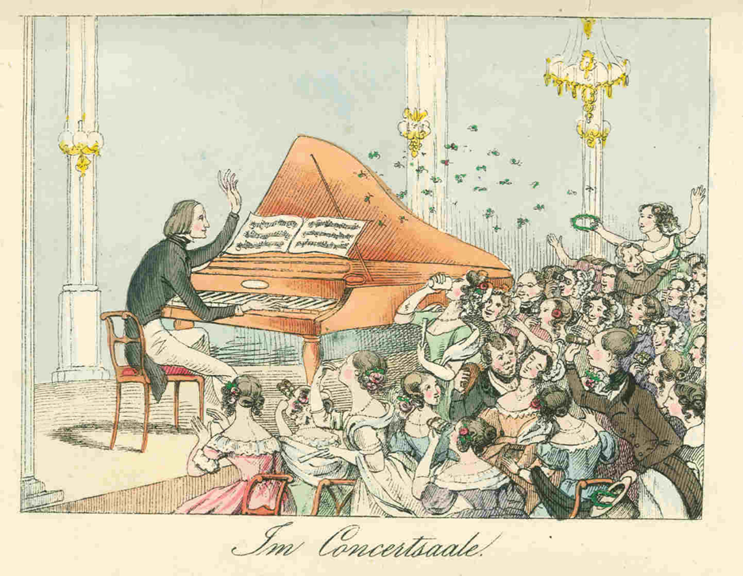

For Franz Liszt, memorization was something that highlighted his status as a virtuoso and a hero who conquers the machine (=piano) in the age of industrialization. In many ways, his place in the history of memorization presents a very different angle from one I shared above. One concrete fact to share, before this gets too long, is the first historical “recital” he gave in London in 1840. The term “recital” comes from the English verb, to recite, implying memorized delivery of a rehearsed, or already formulated, work. The newspaper announcement of the event used a plural form, “recitals” indicating that each piece on the program was to be played from memory!