This is the English translation of my Japanese article to appear in Nikkan San on November 19th, 2021, as a part of my bi-weekly column, “The Way of the Pianist.”

Would you consider sounds insects make “music”? Crickets? Cicadas? …Flies? What about mosquitos?

In the 1970’s, Dr. Tadanobu Tsunoda published papers claiming that native Japanese speakers processed insect sounds in different brain regions from speakers of other languages who seemed to largely process insects as noise. His assertions caught media attention, as well as scrutiny and criticisms about his employed methods, but he has not changed his position, and now his son is continuing the study with updated methods.

Regardless of the accuracy of his study, it is true that Japanese culture cherishes subtlety in their sound environment more than the Americans. For example, in the traditional Japanese tea ceremony, the sound of the water being boiled and poured, and the tea being whisked are all considered a part of the hospitality.

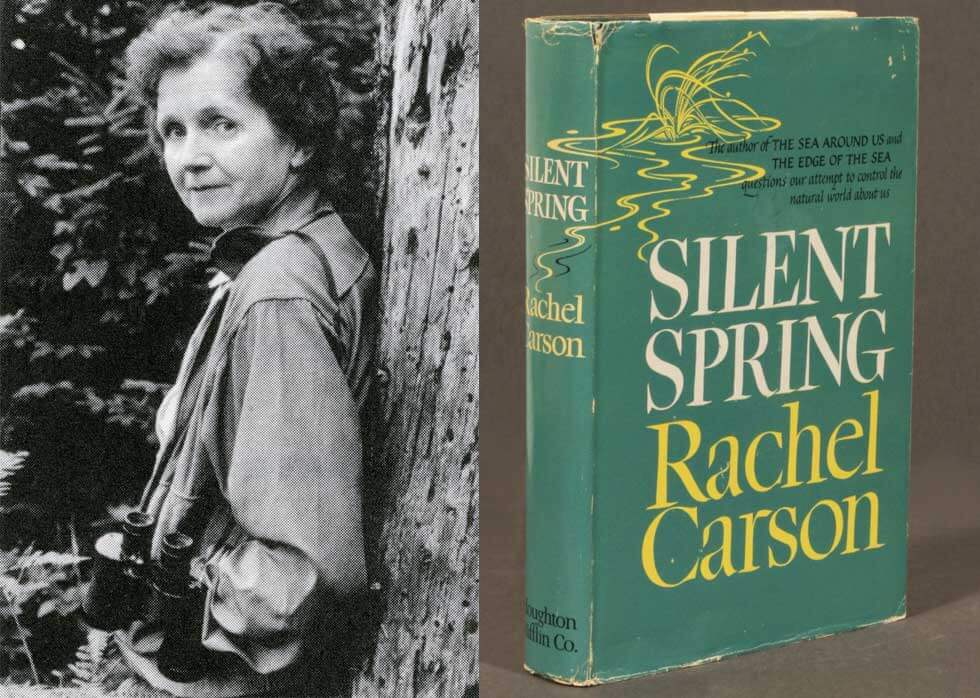

Can Westerners appreciate insect sounds as music, or even language? Apparently so. Acoustic ecology started in British Columbia, Canada in the 1960s to study the relationship, mediated by sound, between humans and their environment. The symphonies of nature sounds they uncovered revealed the loss and damage that we cause our fellow earthlings. Come to think of it, Rachel Carson’s 1962 publication, warning the side effects of pesticides as exemplified in dead birds, was titled “Silent Spring.”

Ears connect us to the world around us on an emotional level. Put your earphones and headphones aside. Raise your eyes from your smartphones. Listen to the sound of the wind, the rain, the trees swaying and the acorns dropping. You would miss even the flies and the mosquitos if they became extinct.