I can still recall many memories from my PreCollege days at Juilliard. One in particular is exceptionally vivid – I can even smell the dusty room, and remember some of my classmates looking up at the teacher on the stage next to me at the piano. He said we were going to run an experiment.

“Imagine,” he started his prompt, “your country is under attack, in the middle of a war. You know that in the audience is an intelligence agent. There is an important piece of top secret encoded in the piece you are about to play, that only the agent knows how to decode. The successful transmission of this information is crucial to the security of your country, and is dependent on your accurate and clear delivery in your performance. The fate of tens of thousands of your fellow country men are literally in your hands.”

My level of focus was heightened, double, or maybe even triple fold. I played from the first to the last note, intent on accuracy and clarity, almost without blinking. My classmates applauded with a loud cheer. I don’t know if it was meant for my performance, or for the teacher for his clever prompt.

Now that I have gained a little bit of insight into the mechanisms of our brain and cognition, I can explain why I recall this memory with special vividness.

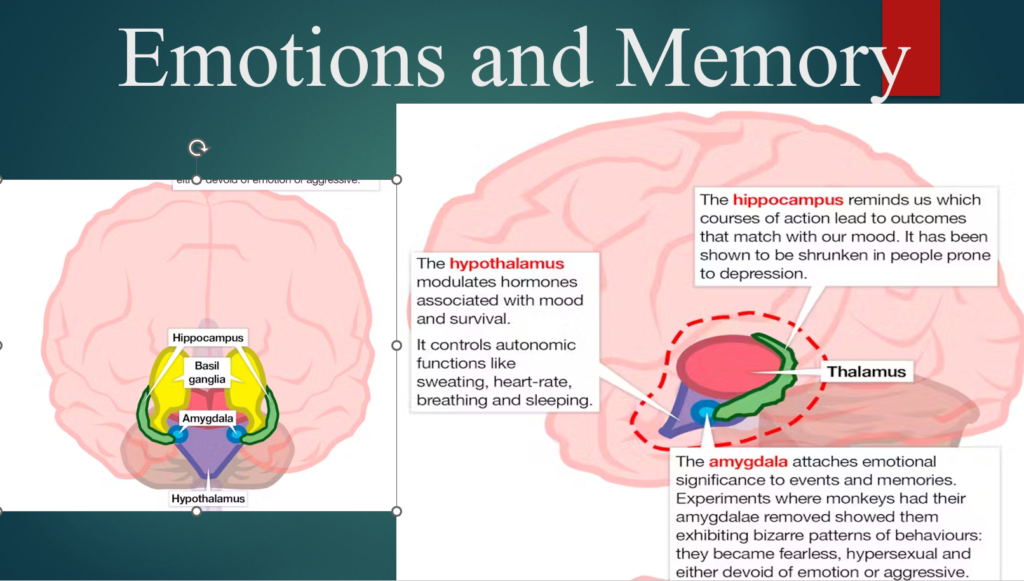

Amygdala, the part of our brain that deals with pleasures/displeasure, emotions and survival instinct is next to hippocampus, another part of our brain that processes input into memories. One of the factors that hippocampus uses to decide whether to retain or discard an input by is signals from amygdala. This is why emotional events, like a trip you enjoyed, or a scary movie are more memorable. You can reverse engineer this to increase emotional association to an event or information, to solidify its memory. That’s what the teacher’s prompt demonstrated. And that’s why music is effective to address challenging issues like climate change, conflicts and disasters, raising not only awareness, but a sense of solidarity, empathy and efficacy.

And now that I am addressing the topic of emotions and memory, I recall a childhood memory. To appease my displeasure at my mother’s unavailability to sit with me for my practice, she told me to “pretend you are playing in front of gods.” I did not grow up with any particular religion, so I immediately thought of men wrapped in white robes, like the people in the School of Athens (1509) by Raffaello Sanzio, and played with my utmost solemnity. In retrospect, I am pretty impressed with my mom’s instinct, considering that this was decades before these studies on the relationship between hippocampus and amygdala!

This blog entry is loosely based on entry No. 124 of my bi-weekly column, The Way of the Pianist (Piano no Michi), for Nikkan San.

Pingback: 美笑日記2.27:感情と記憶の脳内メカ - "Dr. Pianist" 平田真希子 DMA