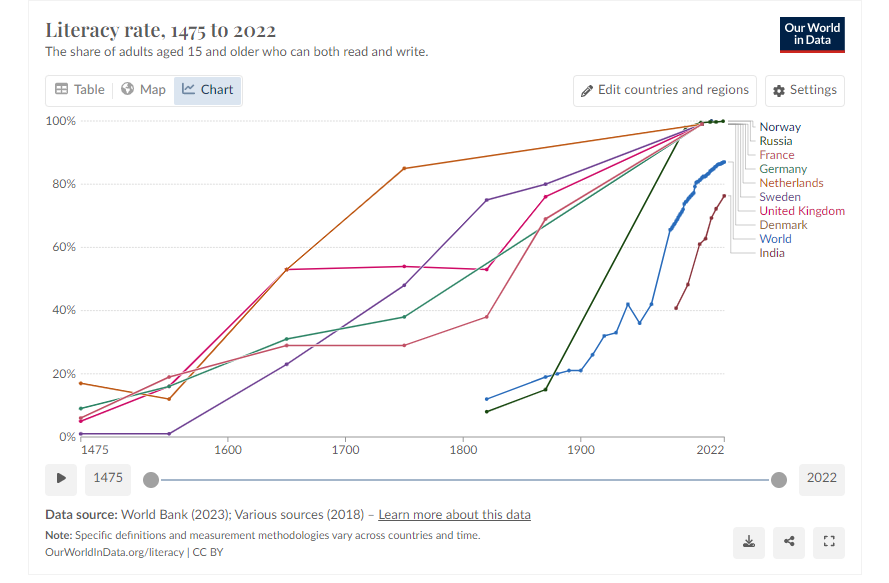

The literacy rate in the global population in 1820 is estimated to have been about 12%. Today, the number is flipped at the global illiteracy rate being about 12%.

Literacy does give one access to information and the ability to develop one’s thoughts, making us more aware of ourselves and our choices. It also expedited the development of science, technology and industry. On the other hand, its side effect may have shifted our priorities from our own senses and experiences to our intellect and understanding, and from our nature as social animals to individualism.

“Lend ears” is a phrase often inserted in medieval texts. Reading was an activity almost always carried out aloud, a kind of performance. Because few were literate. Because in the age of scrolls, before books, there were no page divisions, thus no table of content or index. Finding an information you’ve read again would have required you scrolling through the entire text. That is why you read aloud, moving your mouth, projecting your voice, listening, cherishing the input, often as a shared experience with the listeners around you. However, today, reading is a solitary act, detached from the world, or your sensory experience. When IT can spit any answer to your question instantly, information is disposal, and memories are outsourced to machines. Twenty years ago, we all had memorized dozens of phone numbers. Today, it’s all in the address book in our smartphones.

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, music was considered to exist only in time and in our memories, like all sensory experience.

Since sound is a thing of sense it passes along into past time, and it is impressed on the memory. From this it was pretended by the poets that the Muses were the daughters of Jupiter and Memory. For unless sounds are held in the memory by man they perish, because they cannot be written down.” – Isidore of Seville (560-636 A.D.),

Etymologiarum sive originum libri xx, trans. E. Brehaut

(New York: Columbia University, 1912), 136. Quoted in Piero Weiss, and Richard Taruskin, Music in the

Western World: A History in Documents (New York: Schirmer Books. 1984), 41.

The invention of notation changed all of this, especially the history of Western classical music and its global influence. Notation allowed for a faithful recreation of music that the reader had never heard before. It permitted music to exist independently from human communication and connection, beyond shared space and time. That radical shift became the norm increasingly with the invention of the printing press, and the Industrial Revolution that allowed for the mass production of the instruments and printed scores. And with the invention of phonograph, even a performance can now exist independent of any human involvement, to be enjoyed by a listener in its private space.

When illiteracy was more the norm, people memorized necessary information as texts to songs, using as music as a mnemonic. I feel a sense of nostalgia for the time when people sang aloud memorized information, and read aloud as a performance, just as I firmly believe that the handwritten words are more meaningful, as I type these words on my computer…

Pingback: 美笑日記4・2:聴く文書・読む音楽 - "Dr. Pianist" 平田真希子 DMA