This entry is based loosely on my Japanese article for Nikkan San, a part of my bi-weekly column, “The Way of the Pianist” to be published on June 4th, 2023.

For me, Memorial Day used to signify the arrival of summer, to be celebrated with a cookout with my American parents and their friends. But as I became more aware of my friends’ experiences of wars, as veterans or otherwise, I grew to appreciate this holiday as a day to reflect on the lessons to be learned from our history.

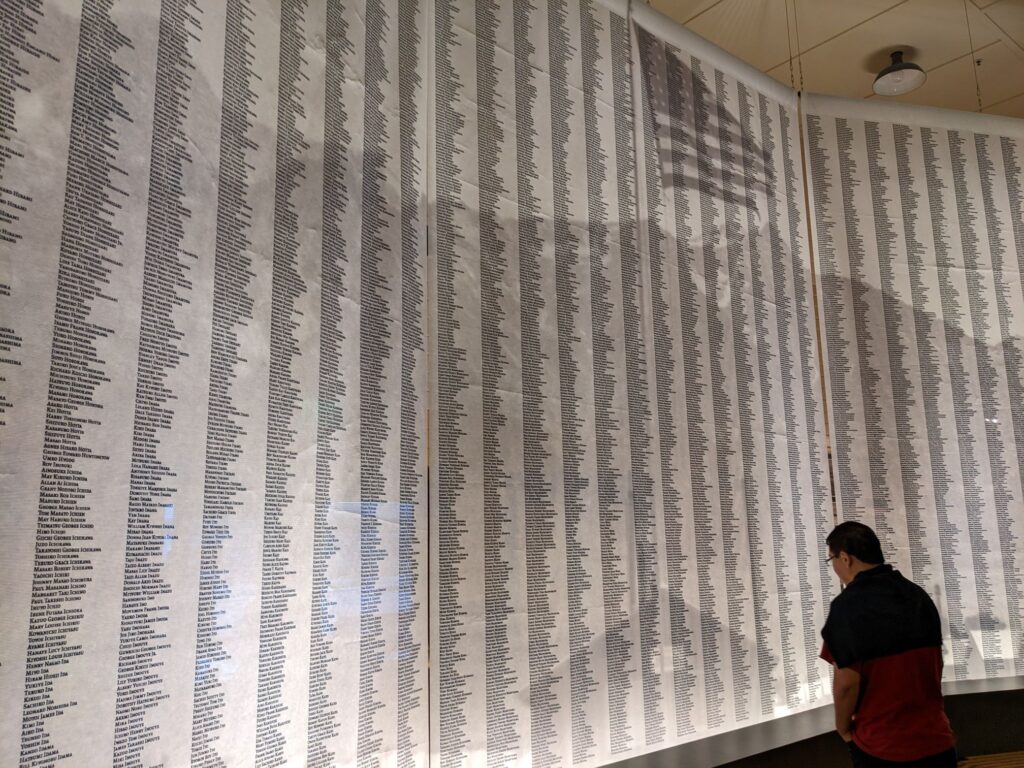

This year, on the Memorial Day, we decided to go to the Manzanar National Historic Site. It housed one of the 10 camps that existed throughout the U.S. to intern altogether more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. There were 11,070 men, women, and children interned at Manzanar between March 1942 to November 1945.

Manzanar is about 220 miles north of Los Angeles. Most of the four-hour drive is through the middle of an expansive desert. There is no water, no landmark, not even a shade one could hide under. Even if someone could escape the camp, it would have been impossible to find help on foot.

Manzanar was established as a national historic site fifty years after its opening as an internment camp. I suspect that it only became possible after President Reagan’s signing of the Civil Liberties Act in 1988. The legislation was a formal apology for the internment and restitution of $20,000 to each surviving victim.

Declaration of Independence famously states that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Recently we have also become more cognizant of the irony that of the 56 men who signed the document, 41 were slave owners. There are too many examples of the contradictions to the ideals of American democracy, starting with the massacre of the native Americans, and slavery. The brighter the ideal, the darker, and the more inconvenient, the irony becomes. “We would be the only ones there…,” my partner and I said to each other as we approached Manzanar, preparing ourselves. Why would anyone want to face a challenging history on a holiday weekend?

That’s why we were surprised. We arrived to find so many cars in the parking lot. Then, it touched us even more when we saw how diverse the people inside were. Older couples. Young lovers holding hands. A group of teenagers in uniform. Some intently reading the explanation next to the displays. Others in front of photos, some with crossed arms, all standing still. I wanted to ask. “What brings you here?” “How long did you drive to get here?” “Why are you spending your holiday here?” But I couldn’t – it didn’t feel right to start a small talk. The atmosphere was not somber – people smiled and nodded at each other, and held the doors open for each other. There was this feeling of comradery, that we were there to learn together. Even the children were speaking in whispers. I heard many languages I did not recognize. So many people, not just Japanese or Japanese-Americans, treated what Manzanar had to offer as something important we needed to examine.

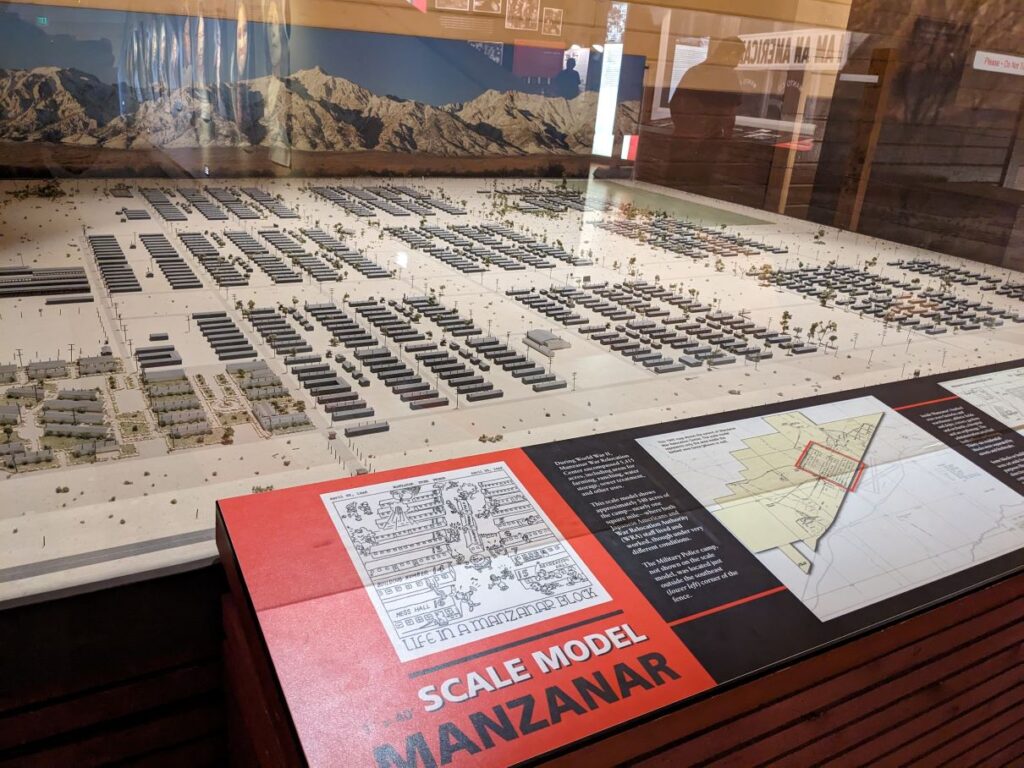

In the 500 acre of designated area, there were 504 barracks in 36 rows. Each barrack was sectioned into four 20′ x 25′ rooms that were assigned to around eight people. Each room had an oil stove, one light bulb hanging from the ceiling, and cots. They were told that desks and chairs were to arrive eventually, but they never came.

Blocks had separate men’s and women’s latrines and showers, laundry and ironing rooms, a recreation building, a mess hall, and an oil storage tank.

The main building of this historic site is the Visitor’s Center. There are a couple of small movie theaters showing documentaries about Manzanar with many interview footage of the survivors. They have photos, paintings, recreated models, and written accounts of the historical background of the Japanese-American internment, and what the lives of people were like in the camp. The building that houses the Visitor’s Center today were built by the carpenters in the camp – it used to the auditorium that could house up to 5,000 for movies, concerts, dance parties, lectures, and ceremonies of various types.

The few remaining barracks recreate the lives of the interned people. They also have stations where you can listen to the survivors’ accounts of what their lives in Manzanar were like. Between March 1942 to November 1945, they did their best to create lives for themselves in the middle of the desert in this internment camp. They established schools for their children right away. Then, they made gardens to grow vegetable, eventually supplying 80% of all that were consumed by its 11,070 residents. They made their own miso, soy sauce, tofu, shochu (Japanese liquor), and pickles. They made everything they needed with their own two hands and the little material they could find.

I could not bare to take a photo of the latrine, so you have to use your imagination. It had no partitions. Toilets were placed next to each other about three feet apart in rows, as were the shower heads next to the toilets. One survivor recalled how her mother refused to take a shower next to strangers, and waited until the middle of the night when no one else was awake.

The laundry room only had a large basin with faucets. People found having to wash their laundry next to each other humiliating.

Strangers were randomly assigned to share a room. Newly weds, families with children…it didn’t matter. There were no materials to build walls for privacy, so some people used their blankets. But it’s the middle of the desert – it’s hot during the day, and freezing at night. I wonder if they could sleep after giving up their blanket for partitions.

The gusting winds were constant, blowing sand into the barracks no matter how much they swept. One survivor recalled how he would wake up, and the only part of his pillow that remined white in the morning was where his head rested – the rest was covered in sand.

People painted murals on the walls of their mess halls.

Many of the paintings recorded the lives and sceneries from the camp. They also made furniture by hand. There were so many little chairs for the children. 541 babies were born in the camp, and many more came as babies or toddlers. They only had cots for furniture, and they were too high for small children to sit on.

Accessories, decorations and toys that women made in the camp. To think that they made so many things, while worrying about their children and elders, and about the war and their future…

Rumors were pervasive and petty disputes were constant. There was a record of rumors going around. “They gathered us together so that when the Japanese military attacks, they can kill us all at once.” “If the war gets worse, they will stop sending supplies and we will all starve to death.” There were so many other rumors about the food ingredients being stolen. Reading through this list gave me a sense of the claustrophobia and helplessness that one could easily succumb to under these conditions.

A photo of a pond, now dry, that used to be a part of a Japanese garden.

Barbed wire and eight watch towers surrounded the 814-acre area, within which the residents built over 100 small gardens. The first garden was complete after less than a month after they moved in, outside of barrack 24. Within the next six months, so many gardens were created that they held a competition!

They were told that the “voluntary relocation” was for their own protection. Over the years, I heard many survivors say how they wondered “if they wanted to protect us, why are their guns pointing at us?” But with the guns pointing at them from the watch towers, they cultivated the desolate land to make vegetables and gardens, displaying their pride and values.

“Even in the most difficult of conditions, you can still choose to remain resilient and resourceful.” I felt encouraged by my predecessors.

There were many paper cranes, a Japanese symbol for world peace, adorned around the memorial.

Excellent choice of location to visit!

After reading the book, “Uprooting Community” by Selfa A. Chew , my respect and admiration for the Japanese people grew all the more so for having endured such horrific treatment. I live in the same city as the author, and she personally gave me a signed copy after I inquired about her book. I recommend this book to all that desire to learn about this sordid history.

Thank you for such a wonderful post.

Manuel

Thank you, Manuel, for your comment and input!

Readers, here is the link to “Uprooting Community” by Selfa A. Chew: https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/uprooting-community

I just read the blurb and some of the reviews.

I did not know about this part of the history, although I always did wonder about the Japanese diasporas in other parts of the wars.